The Good Samaritan: It's more than a lesson in kindness

Behind the familiar story lies a deeper truth about Jesus, the gospel and salvation.

This sermon was given by the Rev. Paul Briggs at Good Shepherd Anglican Church in Cornelius, North Carolina, on July 13, 2025. Pastor Paul, who is assisting clergy at the Church of the Apostles in Charlotte, was our guest preacher on Sunday.

You can view the sermon here, starting 22 minutes into the service.

The text for this sermon is Luke 10:25-37.

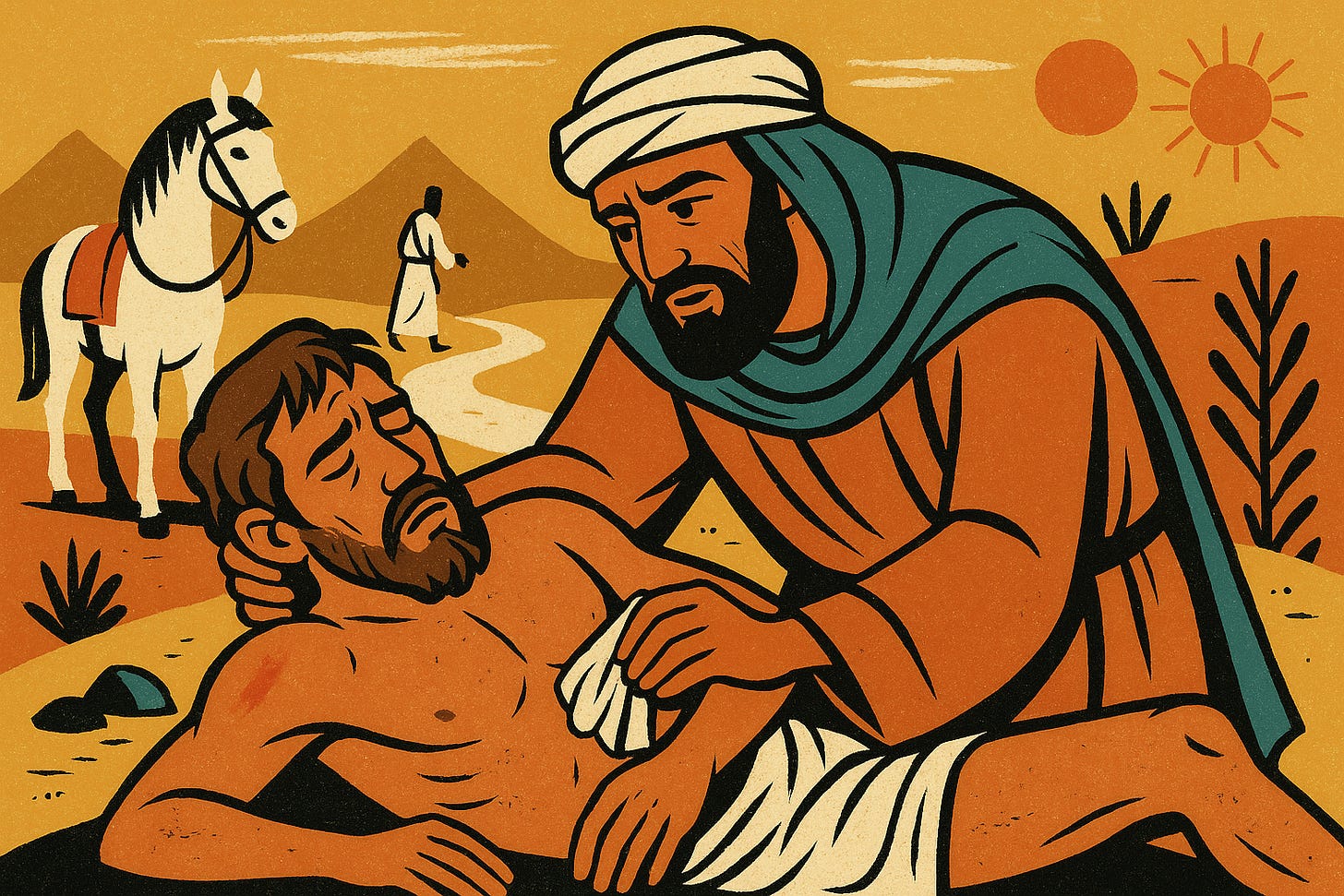

The Parable of the Good Samaritan is one of Jesus’ best-known parables.

Even outside of Christian contexts, the term “Good Samaritan” is commonly used to describe someone who helps a stranger in need.

And that’s what most of us think Jesus is trying to tell us in this parable.

But as often is the case, anything that Jesus says has multiple layers to it — and the Parable of the Good Samaritan isn’t any different.

Here’s a reminder of what the parable is about:

A “lawyer” — likely a religious scholar — challenged Jesus, hoping to expose a theological flaw and diminish his authority in front of others.

Jesus and the lawyer agree that to inherit eternal life, a person must “love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind, and your neighbor as yourself.” (The lawyer combined Deuteronomy 6:5 and Leviticus 19:18).

The lawyer then asks: “And who is my neighbor?”

The lawyer likely expected a narrow answer, as many Jewish leaders of the time tried to limit the scope of that command.

Pastor Paul said:

“Love your neighbor as yourself seems fairly plain. But back then, the established legal interpretation narrowed the definition of neighbor and lowered the bar for obedience by excluding certain groups, such as the Gentiles, such as the Jews who lived in Gentile areas like Galilee, where Jesus lived and where his disciples were from. Samaritans were not ‘neighbors.’ In fact, they were enemies.”

But Jesus responded with the parable of the Good Samaritan, turning the question around and expanding the definition radically — showing that a true neighbor is anyone in need, regardless of social, ethnic or religious background.

In the parable, Jesus says that a man is attacked and left for dead on the road. Two religious Jews (a priest and a Levite) pass by without helping, but the hero of the story — a Samaritan — stops, cares for him, and ensures his recovery.

Seems pretty straight forward, right? When we Christians see someone in need, we should help them, regardless of who they are.

And that’s true. But Pastor Paul showed us another layer to the story.

The Bloody Road

First, I learned that when Jesus starts the parable by saying, “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho,” that this road was commonly referred to as "the bloody way" or "the bloody road" in the time of Christ.

It was a steep, winding, 17-mile route through rugged desert terrain, dropping about 3,300 feet in elevation. Because of its isolated stretches and rocky hiding places, it was notorious for ambushes by bandits.

Jesus’ listeners would have immediately recognized the danger of that road, making the Samaritan’s compassion all the more striking.

The Injured Man

While most listeners would assume the injured man is Jewish because the story is set in Judea, Jesus doesn’t specify his ethnicity or identity.

That ambiguity serves a key purpose: it shifts the focus from who qualifies as a neighbor to how we behave toward anyone in need.

By making the helper a despised Samaritan and leaving the victim’s identity vague, Jesus challenges tribal boundaries and calls for radical mercy.

Also, Verse 30 says the man was “stripped” and “beaten,” indicating he was likely naked or nearly so.

Beaten, half-dead and exposed, he could do nothing to help himself. The scene demanded mercy.

The Priest and Levite

The listeners might expect a priest or a Levite (a person who assisted priests in the temple) to provide that mercy, but they didn’t.

While we view them as heartless, Pastor Paul said there were plausible reasons why they would pass by the injured man.

Ritual purity concerns: Touching a dead body (or someone who might die) could make them ceremonially unclean, disqualifying them from temple duties.

Uncertainty: They may have worried they were stepping into a trap, as bandits sometimes used decoys to lure their next victims.

That said, Jesus presents their actions not as understandable but as failures of mercy.

The Good Samaritan as a representation of Jesus

I thought it was interesting when Pastor Paul said the Good Samaritan could represent Jesus. In fact, Augustine was one theologian who looked at the parable as an allegory. Here’s how:

The wounded man: humanity, broken by sin.

The robbers: evil or the effects of the Fall.

The priest and Levite: the Law and ritual religion, unable to save.

The Samaritan: Jesus — an outsider who shows mercy, tends wounds, and pays the cost for healing.

The inn: the Church.

The innkeeper: the Holy Spirit or church leaders entrusted to care for souls until Christ returns.

Pastor Paul said:

“Metaphorically, what Jesus is revealing to the lawyer with the parable is himself. Jesus comes to the one asking about salvation and offers it to him in himself — treating him with compassion, tending to his wounds, providing nourishment and shelter, and showing extravagant mercy, not just for today, but until he returns.”

Go and Do Likewise

At the end of the parable, Jesus says, “You go, and do likewise.”

That means showing mercy to anyone in need — no matter who they are.

But it also points to something deeper: we are the wounded man, and Jesus is the one who rescued us.

He found us, cared for us, paid the cost on the cross, and promised to return.

When we see that, we don’t just admire the Good Samaritan — we follow him.